Skill ceiling and skill floor theory

SP Intermediate

SP Advanced

SP Expert

Written by Horie, English translation by IIDX.org.

Table of contents

Why do we need to define low and high points?

I don’t believe it’s strictly necessary to spend a lot of energy defining what low and high points are when discussing skill level. In fact, I’m skeptical if rhythm games really necessitate such level of theory discussion.

Nevertheless, you may have spent time in the past analyzing specific gimmicks or memorizing certain patterns of a song to get a better clear or a higher score. In the end, defining what “skill ceiling” and “skill floor” are - isn’t all that different from analyzing a chart. The former is for coming up with a strategy to triumph over a song; the latter is to have an objective view of your abilities to effectively improve your skills.

From this article, the main takeaway should not be the definitions of concepts, but rather an opportunity to look back at your shortcomings and to come up with effective ways to improve on them.

We will use “low point / skill floor” and “high point / skill ceiling” interchangeably in this article.

Defining low and high points

To avoid confusion, the definition of these terms need to be clarified first. To define in abstract terms:

- Low point (skill floor): one’s ability to consistently demonstrate a level of performance within an expected range.

- High point (skill ceiling): one’s ability to (inconsistently) demonstrate a level of performance beyond the typical, not confined to any previously known range.

Pure abstract terms are not easy to internalize, so examples need to be provided to illustrate the point. It should also be noted that definitions of these terms can also vary depending on one’s end goal and the type of game in question.

Using clear ability as a measure of skill

“Clear ability” is defined by your ability to clear a song (getting lamps).

IIDX has stricter timing windows than most other rhythm games, so getting lamps is valued as a strong indicator of skill level. Using this model, we can attempt to define skill ceiling and floor:

- Low point: being able to consistently clear (easier) charts without depending too much on lane options.

- High point: occasionally being able to clear harder charts, sometimes assisted by lane options.

Here, lane options often refer to “good random”, but other interpretations can be valid.

Timing as a measure of skill

Unlike clear ability which only looks at lamps, when timing is used as a measure of skill level, there are a few more factors to consider:

- BPM

- Types of patterns (streams, chords, zure, trill…)

- Note density

- Rhythm (on-beat, off-beat, time signatures, etc.)

Therefore, it’s difficult to have a simple definition of skill ceiling and floor in this context. Just because someone is good at timing low-BPM streams, it doesn’t necessarily mean that they can time on high-BPM streams, or other pattern types but in low-BPM.

While not complete, if I had to define the terms using timing as an indicator, we could say:

- Low point: ability to get near-perfect score on low BPM on specific pattern type

- High point: ability to score well on specific pattern type on high BPM

Dealing with density and different types of rhythm can be naturally improved as you work on your general skill, but getting used to certain types of patterns requires a specific skill set. This will be elaborated upon later.

Games with different gameplay mechanics

The basis can also change if the theory is applied to other rhythm games with different mechanics. For example, in GITADORA, the goal is to hit all notes in a phase to aim for the phase bonus. In which case:

- Low point: ability to reliably get a phase bonus in lower difficulty charts

- High point: ability to sometimes get a phase bonus in higher difficulty charts, with some luck / chance

Characteristics of low and high points

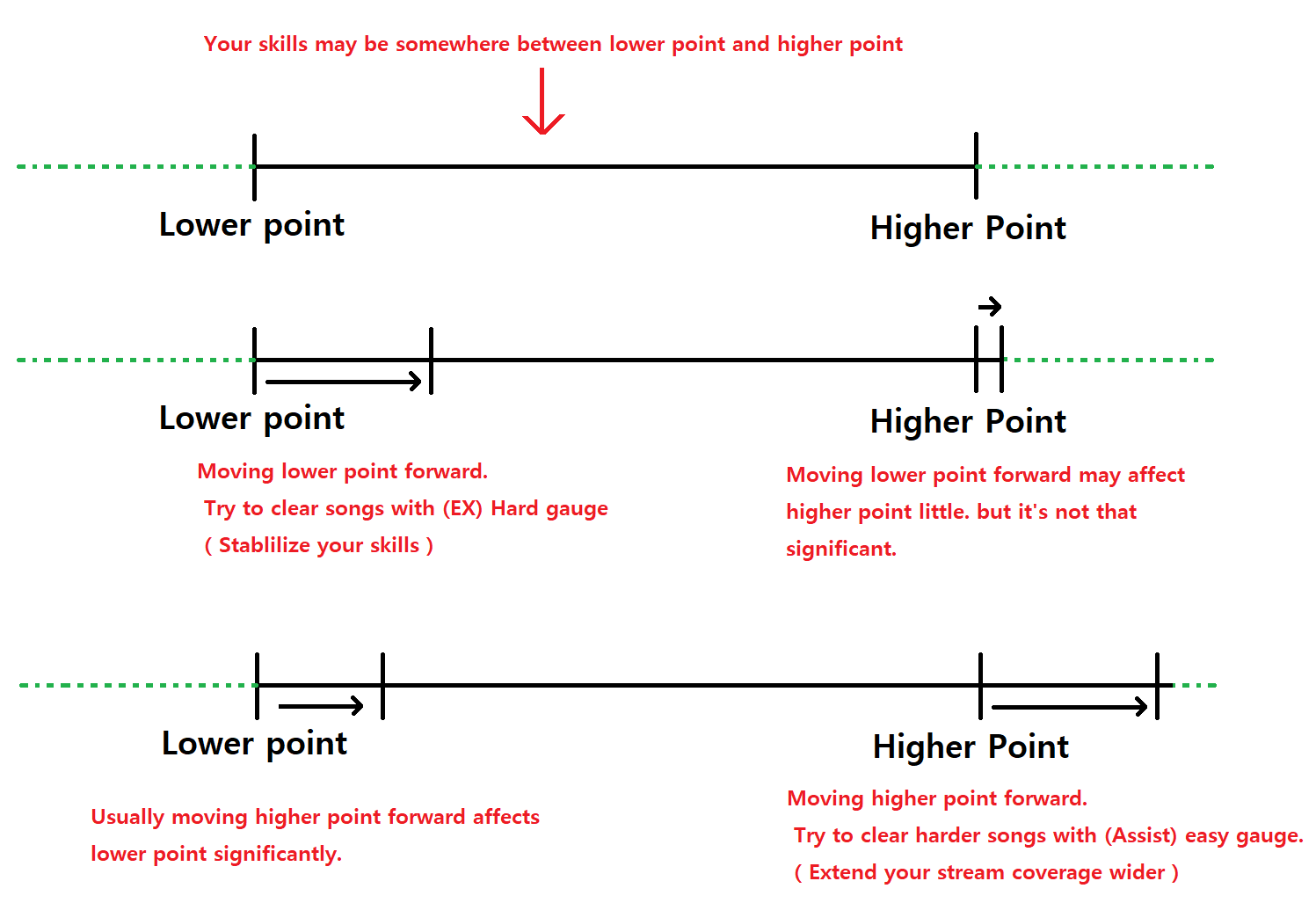

With an understanding that the definition of low and high points can vary depending on context, we can discuss in abstract terms the characteristics of a skill range:

- Your physical and mental condition for the day can affect that day’s low and high points, but it’s not a major factor. You hover somewhere between the low and high points for a given day.

- The skill floor pushes you from the bottom - to a level where you can consistently perform well. It contributes to stability of your performance (the minimum expected level) and reduces the variance caused by “bad days”.

- The skill ceiling pull you upwards, giving you opportunities to clear higher difficulty songs (the maximum, or beyond the maximum expected level).

- Raising the skill floor does not have a huge impact on raising the skill ceiling.

- … but raising the skill ceiling does tend to raise the floor in a meaningful way.

- When your progress stalls, or even worse, when you lose progress over some time - the ceiling decreases first, and after some time, the floor also starts to drop.

- Conversely, when recovering your lost progress, you recover the low point first, but very slowly gain the high point back.

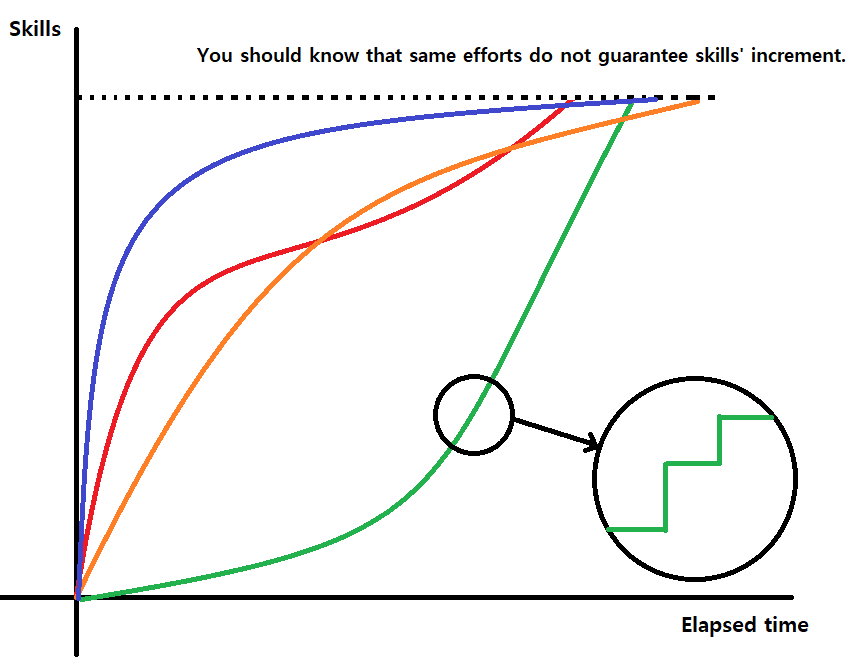

- The rate in which you raise the floor and ceiling is different for everyone, and it’s never linear. On closer inspection, skill increase is more like a staircase function.

Raising the low and high points

- Raising the skill floor and ceiling require repetitive practice in the target tier.

- If you only focus on increasing the floor, the ceiling won’t move much; in fact, the high may even decrease. You become a consistent player, but not enough time to raise the overall skill level.

- If you only focus on raising the ceiling, you could quickly lose motivation to continue playing the game. As another side effect, you become an inconsistent player.

As noted above, it is more efficient to concentrate on raising the skill ceiling rather than the floor - but this only works if you are able to keep your motivation. To maintain interest, you need a constant flow of new achievements (new clears, high scores) that proves to yourself and others that you are getting better overall.

Repetitive plays at increasingly high level is required if you want to focus on raising the ceiling; relatively speaking, compared to the many failures you will encounter as a result of this, you will see few new achievements. As a result, this type of play tires out most players, causing them to gravitate toward the opposite, which is to focus on raising the floor.

Then, it follows that a cycle of pushing the ceiling -> a short cool-down period -> raising the floor is an effective pattern, and you should be planning your sessions around this cycle. Of course, this is speaking in general, abstract terms, so you should tailor the plan that suits your style.

To give more concrete example, here is my “play cycle” :

On weekdays, play BMS 3 days in a row, then rest for 2 days. Play about 3 hours each time.

- Play low tier songs for 20-30 minutes (HEAT) = a short cool-down

- Play mid-high tier songs that I already cleared for 1 hour (RUN) = raising the floor

- Play high tier songs that I never cleared for 1-1.5 hr (RUSH) = pushing the ceiling

- If today wasn’t so great, don’t forcibly keep pushing. Instead, leave things for tomorrow.

Repetitive play sessions without a goal are not an efficient way to raise your skill level. You need to have a concrete plan.

To come up with a plan, you need to recognize your shortcomings. Let’s talk about a few examples.

Bad habits (also known as “curse”, 呪い noroi)

In rhythm games, when you get too used to incorrectly processing specific song or specific patterns, Japanese people call it a “curse”. Here, we’ll call it “falling into bad habits” in English, or “bad habit” for short. You start to fall into bad habits as you force yourself to play similar patterns over and over, and it’s made worse as you force yourself play the same thing even more. Bad habits can be a temporary phenomenon, but in the worst case, you could experience it semi-permanently.

The only surefire way to rid of a bad habit is to greatly increase your skill level, enough to make the problematic song or a pattern trivial at your new skill level. There are also ways to temporarily relieve the effect of bad habits:

- Avoid playing it for a while and come back to it later.

- Try playing the song or the pattern at a low speed, and gradually speed up.

As noted above, once you start falling into bad habits, it’s very difficult to resolve; it’s better to avoid it in the first place:

- Avoid playing the same song or the same pattern too many times over a short period of time.

- Make effective use of random options

Of course, you need to be able to objectively evaluate your own skill level and be able to pinpoint your weaknesses that need to be worked on. Just like in Shogi or Chess, outside observers are able to see better moves than the players. It’s helpful to seek out feedback from players at a higher skill level.

If you really feel that specific pattern types are giving you a hard time, you should try a song filled with that kind of pattern, but starting at low BPM (or lower FREQ option), and gradually raising the speed. Alternatively, you could use memorization tactics to deal with certain parts, a strategy often used in DP.

For more in-depth discussion of this topic, refer to DJ SILENT’s Breaking out of bad habits.

Losing motivation

When you are rapidly gaining skill, you often have a great time clearing many new songs and patterns, keeping you motivated. Once your progress stalls or flat-lines - in IIDX SP, happens around A tier (YMMV of course) - you start to notice how much slower you are progressing relative to before. You would then fall into the trap of playing the same songs over and over trying to get a new clear, ultimately causing you to lose interest in the game. This leads to a vicious cycle of playing the game less, performing at less than desired skill level, and repeat.

The answer is simple. You have to create new goals to stay motivated:

- Play BMS. (also try playing easier songs with high FREQ, or harder songs with low FREQ)

- Use challenge options like S-RANDOM & clearing with them

- (For DP) DBM, DBR

… just to list a few ideas. There are many things you can try to keep your interest, but perhaps taking a break and playing other games is also a good idea. While one may value getting stronger, it’s also important to keep your morale in check so that you don’t end up just quitting it at some point, which would negate any gains you had.

Improving your reading ability (processing density)

To improve your reading, you should raise your skill ceiling by playing charts in the upper tiers. This means focusing your plays to charts with high density that you can barely handle; charts you can inconsistently easy clear. That being said, songs and charts with repetitive elements - such as MENDES or Colorful Cookie - should be avoided. RANDOM options should also be used to increase the variety of note patterns you practice with. Additionally, do not be satisfied with clearing a song once; try to play charts you previously played, aiming for more consistent clears (lower BP).

Improving your timing

Using your density processing ability to clear a song somewhat guarantees a baseline of scoring (in IIDX terms, a mid-tier AA), but learning to time better than that is a whole separate challenge. The recommendation is to learn how to time using charts around your skill floor, being cognizant of different “types” of patterns.

Normally, level 9-10 charts are recommended when starting to learn how to time. For players already at high-tier 12s, they could try level 10-11s instead to learn timing.

Natural aptitude vs. hard work

Unlike the popular saying, putting in hard work will sometimes (or frequently) betray you. Some people are just born with it. Instead, focus on your personal growth.

It would be awesome if everyone achieve their greatest feats, but reality is much harsher than that. It’s only natural to compare yourself to others who are better. To make up for your shortcomings, you might put in even more effort than others - but even then, sometimes catching up is impossible! If this conundrum continues, it affects you negatively, eating away your mental health.

There are ways to overcome this situation - like taking breaks - but if it’s affecting you too much, you should consider quitting. There is one ultimate answer to this though, which is to recognize you are lacking.

Before I got into DP, I played a lot of SP. There were many rivals at my skill level; I frequently compared myself to them, trying to figure out the skill gap. When I realized that this was a destructive behavior, it was already too late.

During all of this, I started to play DP, which helped me escape the cycle of comparing myself to others; in fact, this kept me motivated to continue playing IIDX even to this day. It’s true now, but even then, there were so few DP players that it created an environment that helps me focus on myself only. Now, people who are better than me don’t really bother me much; compared to the past, I’m playing with much more relaxed mindset.

Of course, aspects of the game like Arena mode or Rival system can absolutely provide an environment that encourages friendly competition, which can serve as a big motivator to push you forward. Nonetheless, it should be noted that there can always be too much of anything; if you’re getting tired from the competitive nature, you should shift your focus back to you, comparing current self to your past self.